We cannot reduce every major global economic development upon US President Donald J. Trump's tariffs just yet: rhetoric still prevails over direct ripple effects. Nevertheless, if history is any guide to causal-consequential global commercial developments, particularly if they happen to be economic, the China-Japan October 2018 thaw may be not only an unintended product of US tariffs, but it may also release more globe-rattling ripples than its cause.

Korean peace was at stake, as too the East China Sea disagreements. Both probably rank among the issues of titanic importance to East Asian and global peace. Notwithstanding Trump's noisy North Korean breakthrough over the year, how both North and South Koreas have taken off with peacemaking gestures of their own stand to steal the show. It alone may be more than reassuring to an increasingly impatient China and alarmingly concerned Japan. With Trump's hawkish cabinet change-of-guard, it may be hard for Kim Jong-un and Trump to embrace each other as spontaneously with the same warmth as before: as both Korean leaders hob-nob each other, China and Japan may reap even more benefits in their fraying relationship.

Over the volatile East China Sea disputes, Japan's Shinzo Abe and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang made "stability in the East China Sea" pivotal to "genuine improvement" of bilateral ties. Yet, since relations were suspended in 2011 after tense standoffs, China and Japan have reassuringly gotten back together over the negotiating table. Not that that will solve bilateral disagreements, but the start made at so propitious a moment opens space for the ice-breaking economic agreements.

Both the world's second and third largest economies decided to function more collaboratively, in no small part owing to the tariffs imposed by the world's largest economy. Trump's tariffs were punitive, but if the Sino-Japan rapprochement reading is correct, some very Asia enhancing, global wealth distributional consequences may be in store.

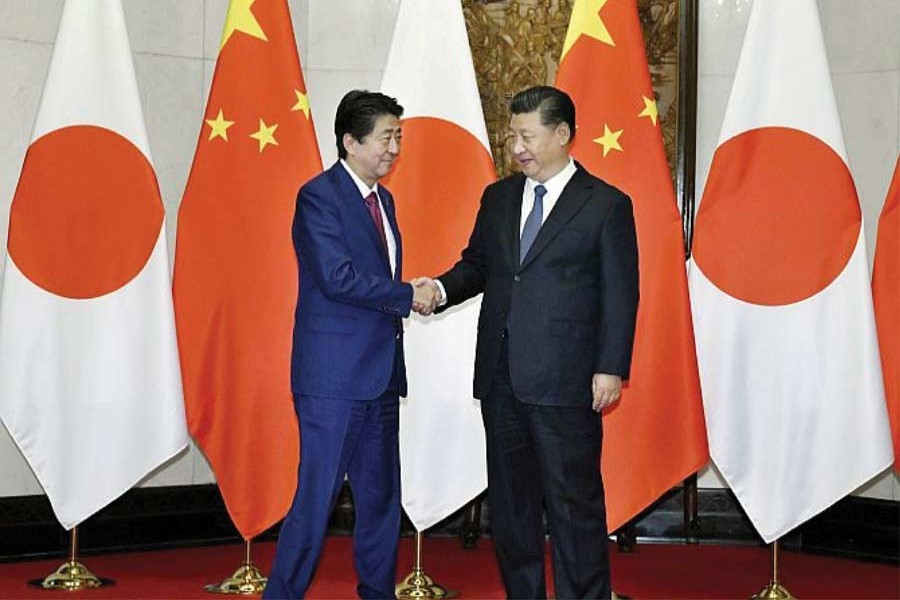

A wide-range of agreements was signed even before Abe met China's President Xi Jinping. The first such summit since both Abe and Jinping consolidated personal power in their respective countries got off to a roaring start: a $30 billion currency-swap agreement was signed, valid until 2021; a yuan clearing bank was established; cooperation in the securities market began by listing exchange-trade funds (ETFs); free-trade was targeted, with the promise to renew negotiations on the stalled Regional Comprehensive Economy Partnership (RCEP); and a China-Japan-Korea trade zone sealed the deal. Lubricating state-state cooperation were 500 deals between Chinese and Japanese corporations, worth up to $18 billion. China seeks Japan's endorsement of its Belt Road Initiative (BRI), while Japan seeks more Chinese markets, especially for its automobiles, given the nature of Trump's tariffs.

Those US tariffs could not but release incorrigible forces. Japan might be highly favoured in Washington, as indeed, Abe became one of the first, if not the first foreign leader to meet Trump after his election. Nevertheless, Trump's reckless handling of his tariff weapon immediately caught policy-making eyes in Tokyo, and as those tariffs increasingly show signs of shifting from country-specific punishments to all-bracing economic enhancement measures, Japan's concerns may be turning into worries.

China being directly and blatantly hit with escalating punitive steps also feed into Japan's fears: it faces what the media calls 'collateral damage', perhaps as a premonition to those very punitive actions being applied later. After all, the anger against China among US consumers today is not far different from the 1980s Japan-bashing outbursts. China has threatened retaliation and refuses to blink. Japan does not have the option to do either: it faces direct military threat from North Korea, growing challenges from China, threatening to even isolate Japan commercially, and a United States suddenly looking like a slippery and untrustworthy ally unlikely to come to Japan's defence in the same way Trump is threatening to abandon West European allies through NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) disengagement.

Abe's Beijing visit, first of all, implicitly acknowledges China's ascendancy. That is the only reason why China is willing to put the East China Sea disputes on the back-burner. Secondly, China is beginning to feel the initial effects of the tariffs: its dollar reserves have begun to dwindle, in turn elevating BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) costs and slowing domestic economic restructuring efforts, for example, to shift towards a more liberal trade policy approach, as Jinping promised at the 2017 World Economic Forum in Davos. Thirdly, China sees the opportunity to establish its leadership in East Asia, and in the near future, all of Asia, but to claim it, cooperation has been adopted as the means, not just with Japan, but as we saw in the Wuhan Summit earlier this year, India as well. Finally, Japan is a far larger market than China has been able to access (as is also true of China's market for Japan), and with US trade restrictions, China's new market-accesses needs spiral into a priority to avoid slowdowns and disruptions in its own economy. Any faltering on the economic front would loosen China's inevitable rise to leadership on this front: with a BRI network already catering to just under a trillion-dollars worth of trade, adding Japan will help China both reach that self-declared goal and compensate for losses incurred under a Trump presidency in the United States.

All things being equal, that is, no interruptions interrupting this status quo, both China and Japan will be able to shift the loci of both economic and political power to Asia. China's desire to do so is already clear in the BRI project, which, in its fifth year, already has a large part of South and Southeast Asian countries cowing down before China. Japan's desire is also not any less: it is more transparent, particularly the economic and military deals it has concluded with India and collaborations with both India and the United States across the Indian Ocean.

One immediate spin-off of this China-Japan summit would nudge both Koreas to forge closer relations, neutralise and eventually demilitarise the 38th Parallel, and boost outwardly-diffusing economic cooperation. The more they do so, the less likely the sine qua non US presence will remain so. China has effectively cooled off Kim's enthusiasm in ballyhooing with Trump; but if the two Koreas push corporation-level cooperation more arduously, the likelihood of a trade-zone may be a lot higher than one might have reckoned last year when those missiles were flying out of North Korea over and onto Japan. Even an ascendant Korea would strengthen the Asian power-axis, and in all likelihood, against US preferences.

In short, the immediate-, medium-, and long-term consequences have been carefully calibrated in both Beijing and Tokyo to not only make this summit happen now, but to also let it speak for many, many more years to come since the US policy approach is being perceived for not changing much over the long-haul. The upshot of it all is that both China and Japan also have a Plan B without each other which disturbs each other so much that they do want Plan A to work out well. If the present concern is economic, the overall and underlying fear is military security.

A series of Scopus articles in November addresses world leadership's evolving necessary condition of military security to permit the sufficient conditions of economic and technical growth possible across Asia.

Dr. Imtiaz A. Hussain is Professor & Head of the Department of Global Studies & Governance at Independent University, Bangladesh.