France may not be as unlikely a player in an Asia-centred global power rivalry as one might believe. It has the largest colonial leftovers in the Indo-Pacific Region (IPR) than any former European empires. Like other western countries, it has expressed concerns over China's rapid rise into the leadership slot, but unlike them, it also faces stiff Chinese competition in the one continent it often believes to be more Francophonic than any other: Africa. Most of all, like many ascendant or declining middle-power country, it feels the simultaneous rise of China and US indifference/decline demands standing up and shaping whatever the outcome. The net effect of an economically struggling France striving to reflag a stranded post-Brexit European Union has been to push political/military stakes up far more than their economic counterparts, hoping the investment is marketable enough.

Whether they pay off or not, much is at stake: economic progress might have to be kept on hold for a little too long to sort out the changing global order, especially with Atlantic zone powers too much on the defensive and with precious few resources to manipulate. Commanding over 2.5 million square kilometers of an IPR Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ), as per the UN Conference on the Laws of the Seas provision, France has more colonial clout left than Great Britain (in whose empire "the sun would never set"), and an area it knows only too well from its 1960s-1990s nuclear missile tests. In the Indian Ocean it has Mayotte and Réunion, not to mention naval bases in Djibouti (precisely where China has one and Japan has dispatched a Self-Defence squadron), Abu Dhabi, and Réunion itself. In the Pacific, its territories include French Polynesia, Nouméa (New Caledonia), as well as Wallis and Fatuna Island. As a late 19th Century industrial coloniser from Europe, France stubbornly holds on to all that it can; and what it has, though measuring barely 2.0 million people in all, gives it outsized clout.

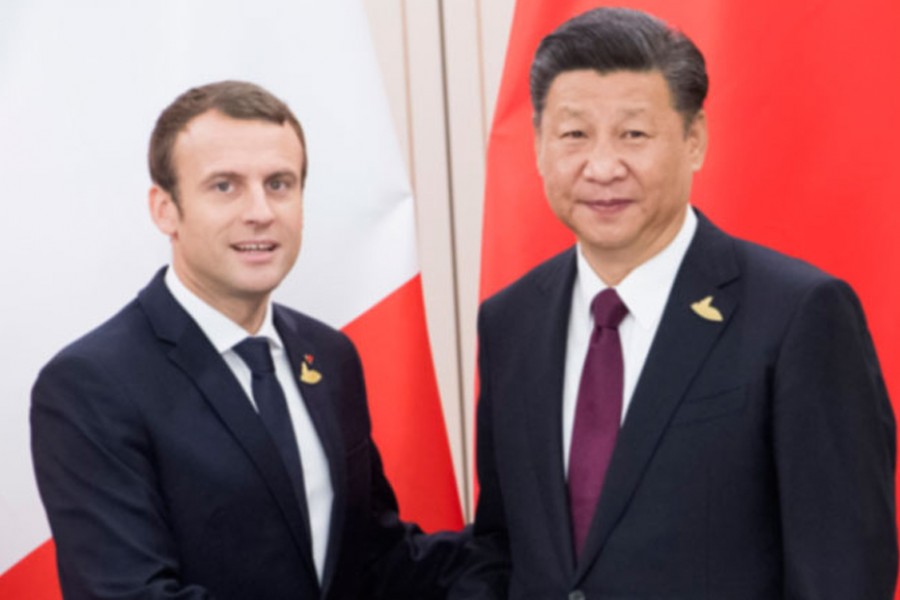

It may still be appropriate for France to speak up. President Emmanuel Macron began 2018 with a visit to China to diplomatically caution that country how its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) ought not to be a "one-way" project. Two months later he returned Narendra Modi's 2017 France visit, and two further months later, he landed in Australia. In both he elaborated what to do against that "one-way" project. By the time of his Australia visit, the 'Asia-Pacific' term had been widely replaced by 'Indo-Pacific', much noise was drummed up behind "fellow democracy partners" (reminiscing Franklin D Roosevelt and Winston Churchill in the August 1941 Atlantic Charter), and Macron openly championed a 'Paris-Delhi-Canberra axis' as being "absolutely for the region and our joint objectives in the Indian-Pacific region."

These initiatives did not just fall from the sky, and Macron was not even the leading light. Even before his 2017 election, Australia decided to purchase $39 billion worth of submarines from France (from the Naval Group company), a process that keeps the two countries wed-locked until 2050, at the least, meaning defence deliberations have been given a long-haul bilateral time-frame, and during which, given the size of this purchase, relations can only deepen. Earlier in 2016, Australia's Defence White Paper identified France as one of the country's closest collaborators (along with other QSD partners, often referred to as the QUAD): Japan, New Zealand, and the United States, with India entering subsequently, while France's New Caledonia and Polynesia were admitted into Australia's Pacific Island Forum.

Also in 2016, in fact on India's Republic Day on March 26, President Francois Hollande visited India, one resulting in another multibillion dollar defence deal: purchasing French fighter planes, even producing them in India through an alliance between India's Reliance Group and Dassault Reliance Aerospace Limited from France. In the air and on the sea, the two countries have a lot going on which no BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) manager can ignore. France sees in its Asian connections the leeway to surge ahead of other European partners, even the United States, should the superpower seriously retreat globally; and both Australia and India see an established nuclear power like France compensating their weak-spots locally. If the United States climbs on board, a formidable alliance could emerge to rank nearly as high as the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) once did; but these initiatives carry the hallmarks of standing solo, that is, in case the United States retreats.

Clearly two sharp global observations have been made: the United States approaching the brink of retreating from its global commitments/operations; and China standing on the doorstep of global leadership. Nothing frontal is being done to stop or reverse China's power from progressing, just as not one iota of energy is being spent to encourage the United States to reconsider its calculations. These are all players promoting their own vested interests, knowing full well (a) they need China too much economically to taint any bilateral relationship with that country; and (b) they are not alone, meaning one can shop for allies as one desires.

They have Great Britain and Japan to draw upon, for example, but as Modi's summit with Xi Jinping in Wuhan earlier this year indicated, and Shinzo Abe's similar summit with his Chinese counterpart in October 2018 reiterated, each is also open to pushing their own interests with China irrespective of their "fellow democratic partners." This is as classic a balance-of-power setting as one can find, this time anchored in Asia, not the Europe where it made its name and explained several centuries of political developments. It is also too delicate and complicated to sustain itself given the collateral collusions possible: India, for example, is very friendly with Russia, which is itself in far more arrangements with China than India, and a country West Europeans have gotten too wary of given the Ukranian intervention and poisoning dissidents abroad, as in Great Britain recently. All of them straddle emergent Middle-East fault-lines, with the US sanctions on Iran being defied by them all, or given temporary exceptions by the United States, with Australia, again, standing apart. Even mentioning Iran generates feelers in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel, where many of these countries follow quite dissimilar positions (over Palestine, punishing Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman for the Jamal Khashoggi murder, or engagement in the Syrian dismantlement processes, obviously for different reasons), in spite of their common Iran-based apprehensions.

With shadow effects ringing any moves by any of these players, China's progression is unlikely to be seriously constrained; and since China's firepower thus far has been substantially economic at a time when all these naysayer countries have been building their political/military resources, the end-result may, in true Shakespearean sense, prove to be too much sound and fury, ultimately signifying nothing. Or it may emanate from a tyranny of errors, that is, one unwitting false move setting off a domino effect.

What it does for France is to elevate the country at a very difficult time: not only is the president facing increasing domestic hostility even after leading his party to victory in both executive and legislative elections, but France's economic problems are just too big for military arrangements elsewhere to conceal this inherent predicament, worsened, as it has been, by a precariously slipping European Union and the end of a stable Merkel era.

As this Scopus series shows, holding economic advancement, and thereby collective interests, to self-seeking political calculations is spreading like wildfire across the international system. In part this is because of a perceived leadership vacuum. Yet there may be too many contenders or pretenders to retrieve or enhance stability. Some country must yield somewhere for a successful transition. Or a collective outcome may hold the key. The final two pieces of this series examine precisely that option.

Dr. Imtiaz A. Hussain is Professor & Head of the Department of Global Studies & Governance at Independent University, Bangladesh.